Samsara

Ignorant V Wise

sokasthana sahasrani bhayasthana satani ca

divase divase mudham avisanti na panditam - Mahabharata Vanaparva 2.15

In the Mahabharata, Rishi Saunaka advises the grieving Yudhishthira, who has unjustly lost his kingdom to the Kauravas, by explaining a profound truth: thousands of sorrows and hundreds of fears overwhelm an ignorant person daily, but not the wise. This is something we can easily observe in our own lives:

What will happen to my family without me?

I’m more dedicated than others, yet they are more successful.

If only I could be with this one person, I'd be happy.

I’ll be secure with millions in the bank; until then, life is painful.

Why am I the one suffering, despite being a good person?

No matter how hard I try, nobody appreciates me.

I wish I had taken care of my health when I was younger.

The list of such concerns is endless.

Why is it that only the ignorant are afflicted with so many sorrows, while the wise are not?

It’s important to understand that the wise are not immune to pain and pleasure. However, they understand the true nature and cause of these experiences. This understanding prevents them from being disturbed by life’s inevitable ups and downs. In contrast, those who dwell on their pains magnify their suffering. In an attempt to escape, they seek pleasure, but in their ignorance, they become attached to these pleasures. This attachment results in further suffering, as they constantly fear losing what they have gained.

Nature of the pains

matra sparsatu kaunteya sitoshan sukha dukha dah

agamapayinonityah tams titikshasva bharata - Bhagavad Gita 2.14

In this context, Krishna emphasizes that titiksha (endurance) is crucial for a yogi on the spiritual path. When the senses come into contact with their respective objects, it naturally leads to the experience of dualities—pleasure and pain, heat and cold, success and failure, like and dislike... Krishna encourages us to understand that these dualities are impermanent; they come and go as part of the life.

Consider some of the moments in your past that have shaken you deeply—losing a loved one, facing failure despite your best efforts, or being betrayed by someone you trusted. At that time, the emotional weight of these experiences might have made you feel as though you'd never escape their grip.

But now, with the benefit of hindsight, you can recognize that while these events caused immense pain, you eventually moved forward. They are no longer part of your present reality but exist only in memory. This same impermanence applies to pleasurable experiences as well.

When we magnify our problems, they seem overwhelming and insurmountable. However, when we shift our perspective, we begin to see their true nature—they are temporary and fleeting. If you don’t change your perspective, these circumstances will continue to dominate your mind, trapping you in their influence. To practice and progress spiritually, one must first break free from the spell of these temporary emotions.

Krishna acknowledges that this is not an easy task, which is why he points out how rare it is to find a yogi. Out of thousands, only a few even strive for this spiritual path. And among those who do, only a rare few actually succeed.

manushaynam sahasreshu kascid yatati siddhayoh

yatatam api siddhanam kascin mam vetti tattvatah - Bhagavad Gita 7.3

Samsara (in brief)

[Refer to Sivam - Sadhanapada 12 (Vol. 2) - A commentary on samkhya and yoga by Dr. V. Nagaraj]

Our mind has the potential to store deep-rooted impressions, known as samskaras, which are shaped by our past karmas (actions). You can think of samskaras as the “seeds” of our actions. For instance, when you see an attractive person, it triggers the samskara of “liking,” which then evolves into a desire, pushing you to act (commit karma) to be with that person. This action, in turn, reinforces the samskara of attraction, trapping you in an ongoing cycle of karma and samskara:

… samskara → karma → samskara → karma …

Though we may dedicate our entire lives to fulfilling the desires driven by our samskaras, we never fully satisfy them. Since one lifetime is insufficient to fulfill our endless desires, we are reborn into another body and begin the process again. Thus, we become trapped in the eternal cycle of samsara (the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth) with no apparent end in sight

… samskara → janma (birth) → karma → samskara → janma → karma …

In his commentary on the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, Shankaracharya compares samskaras to a leech. A leech first attaches its posterior sucker to one surface and draws blood. Once its anterior sucker is securely attached to another surface, it moves forward and begins sucking blood from the new spot. In the same way, samskaras take up one body to fulfill desires and dislikes by committing various karmas. When the body can no longer sustain these actions, it is discarded, and a new body is assumed to continue the cycle.

Samsara (elaboration)

According to Patanjali yoga sutras 3.18, once a yogi acquires the faculty of samadhi (eighth limb of ashtanga yoga), he can use that faculty to acquire knowledge about the origin and the development of a particular samskara (deep-rooted impression) across the previous lives. The great sages who have understood the cycle of samsara through their yogic powers have shared their wisdom to guide future generations on the right path.

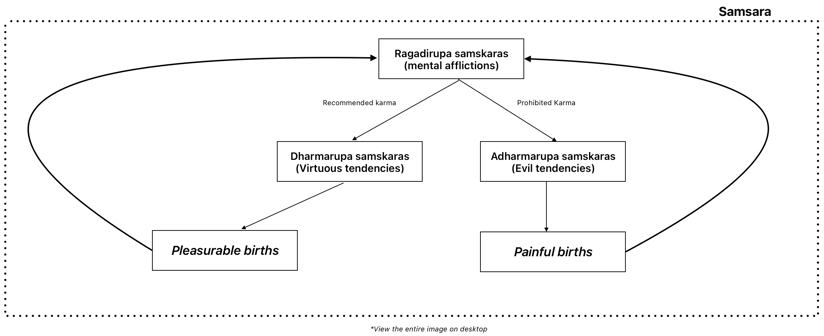

The root of our suffering lies in the mental afflictions (ragadirupa samskaras) that we carry over countless lifetimes. These afflictions are what push the mind outward in order to feed the mental afflictions:

Kama (strong desires)

Krodha (anger)

Lobha (greed)

Moha (delusion or lack of discernment)

Madha (pride)

Matsarya (jealousy)

These afflictions sometimes lead to the performance of good karmas (virtuous actions), which not only benefit the individual but also those around them, including animals, plants, and the ecosystem. Such actions generate dharmarupa samskaras (virtuous tendencies), which purify the mind. The more we engage in virtuous deeds, the more peaceful and clear the mind becomes, preparing it for spiritual practices.

According to the doctrine of karma, virtuous actions lead to favorable births, where one may be born into a prosperous family, enjoy good health, have a healthy mind, or possess exceptional talents from a young age (like a child prodigy). In exceptional cases, virtuous deeds can result in being born as a celestial being (devata).

On the other hand, when desires, anger, and other afflictions overpower one’s discretion, they lead to harmful actions that cause suffering to others. Such sinful actions produce adharmarupa samskaras (evil tendencies), which trap individuals in a cycle of suffering, leading to painful rebirths.

This explains a common puzzle in society: why do good people often suffer while those who commit harmful actions seem to thrive? The answer lies in past karma. This is exemplified in the Mahabharata, where the righteous Pandavas suffered immensely, losing their kingdom and enduring 13 years of exile, while the evil Duryodhana thrived during the same period. However, in the end, the Pandavas regained their kingdom, while Duryodhana’s greed and jealousy led to the downfall of the Kauravas. Understanding karma helps us to live morally upright lives, and even if one is skeptical about the concept, doing good has no downside.

Whether one engages in good karma or bad karma, the result is the same: rebirth. After each birth, one accumulates more karmas, which continue to feed the afflictions, resulting in a cycle of favorable and unfavorable rebirths—over and over. Thus, samsara remains uninterrupted.

brahmadisu trnantesu bhutesu parivartate

jale bhuvi tathakase jayamanah punah punah - Mahabharata Vanaparva 2.68

The cycle of rebirths is not limited to human forms alone. In the Mahabharata, it is mentioned that the range of rebirths extends from the smallest, most insignificant forms, like a blade of grass, all the way to Brahma, the creator. One may be born in water, on land, or in the air, repeatedly circling the entire universe through various forms.

What determines whether we are reborn as lower species or higher beings?

How can one attain rebirth as Brahma, the creator? Isn't Brahma considered a god?

How can the eternal cycle of samsara be broken?

Is liberation from samsara only possible for yogis, or can ordinary people living in society also find a way out?

Where does one begin?